This story is included in the most recent issue of Quest Magazine, the College's twice-yearly Alumni publication. To view the entire issue online, or to view longer-form "Quest Extra" pieces, click here.

Alex Provant had not yet finished his first semester at The College of Idaho when a professor asked him to consider participating in an important history project.

Flattered at the invitation from Dr. Rachel Miller, professor of history, and aware of the project’s potential, he took the leap. “I thought it was a great opportunity to get involved with research,” he says.

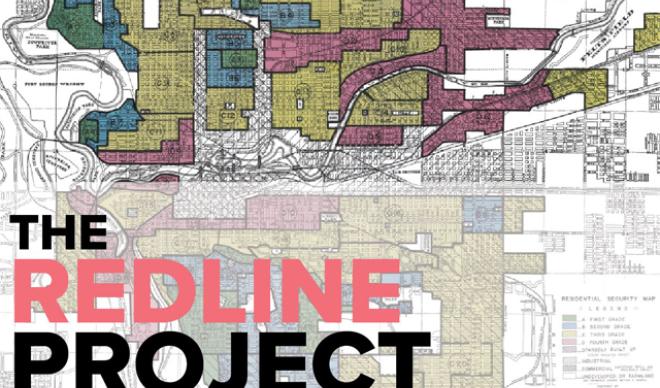

A year later he finds himself immersed in the Redline Project – although his research helped prove that to be a misnomer. The project allows him to do important historical research. It can educate people across Idaho about the state’s history and can influence decisions they make for their future. And it has already helped persuade Idaho’s usually contentious Legislature to pass a law by an exceedingly rare unanimous vote.

Miller calls the project she pitched to Provant “a pretty unique combination of research and advocacy.”

It is also a perfect example of the College’s High Impact Practices (HIPs) that guide students in applying their education outside the classroom. As in Provant’s case, that guidance is not limited to junior or senior scholars but begins as soon as students step onto campus.

Setting the research goal

Originally Provant and his teammates were tasked with researching the history of redlining in Idaho. Redlining is an illegal discriminatory practice in which mortgages and insurance are denied to people – particularly people of color – who live in certain neighborhoods that the federal government identified as high risk.

The project grew out of a conversation between Vice President of High Impact Learning Latonia Haney Keith and Director of On-Campus Experiential Learning McKay Cunningham in the HIPs department. They were curious after checking out the “Mapping Inequality” interactive platform posted in 2016 by the University of Richmond (https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining). It uses Home Owners’ Loan Corporation information to map redlining across the United States.

“We looked at Idaho, and it was completely blank,” Cunningham says. “We thought, ‘This can’t be right.’”

They recognized an opportunity: Students could fill in that blank by unearthing redline maps to see how government policies affected neighborhoods across Idaho. The team, then comprising four students, dug in – and learned that no such maps existed. Apparently, Idaho’s cities were just too sparsely populated at the time for the government to bother with mapping them. (In 1930, Idaho had fewer than half a million residents, and Boise, its capital and largest city, was home to slightly more than 20,000 people.)

Adjusting the scope

Undeterred, the team adjusted the project scope, embraced a broader understanding of redlining, and dug into historical documents. They found discriminatory language in Idaho was contained not in government-inspired mortgage rules but in the covenants, conditions & restrictions (CC&Rs) attached to subdivisions. These legally binding recorded documents prohibited people of color from inhabiting properties in the subdivisions the CC&Rs governed – unless they were domestic servants.

Turning their attention to Ada County, the state’s most populous county and home to Boise, the students found the language in CC&Rs for 50 different subdivisions – some as small as a few properties and others as large as 250 homes.

Meanwhile, Idaho Sen. Melissa Wintrow, D-Boise, had been contacted by a concerned constituent who had stumbled upon the language attached to his property. She began working on a law to allow people to change the racist language attached to their property without going through a lengthy and expensive legal process. She heard about the Redline Project and reached out to the College’s team, which became intricately involved in the writing and passage of Senate Bill 1240. Cunningham and some of the student researchers testified at legislative hearings – and attended Gov. Brad Little’s signing ceremony after the bill’s passage in early 2022.

“Instead of just talking, we did something,” Cunningham says, adding that students “are willing to do the tedious work in order to achieve the longer-term goals.”

Shaping the future

Those goals include continuing to unearth racist language in CC&Rs across the state, educating Idahoans about the existence of such language, and helping homeowners to eradicate it. The team plans to post an interactive map where Idaho homeowners can learn whether such language is attached to their properties. They hope to link that map electronically to the county clerk’s offices where homeowners can apply to have the language removed.

While the discriminatory language was deemed illegal – and thus unenforceable – by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948, it continued to be embedded in Idaho CC&Rs long after that and will remain attached to individual property deeds until homeowners act to remove it. Provant says that action is important, noting that the team has heard from people who bought homes and then found the language. “Just having that in the documents makes them feel unwelcome in their own homes,” he says.

Team goals also include learning how and why the language came to exist. “It’s not about assigning blame or characterizing people as good or bad,” Miller says. “It is about studying who came before and why they did the things they did. People make choices for reasons, and we want to know what the reasons are.”

Miller sees the research expanding to look at other programs, such as homestead claims, that affected access to real estate. “This is just one little piece of how land was bought and sold,” she says of the CC&Rs. “We could all spend the rest of our lives studying the fundamental questions that motivate the project.”

Provant notes that the team can incorporate demographic information to study “how this affected the development of the Boise Valley over the last 70 to 80 years.”

The Redline Project started with four students and has grown to 16 – including first-year students to seniors, Idahoans to international students. Some students hold paid research positions while others, including Provant this semester, hold internships that require additional reading and study to gain academic credit.

The College of Idaho has a 132-year-old legacy of excellence. The College is known for its outstanding academic programs, winning athletics tradition, and history of producing successful graduates, including eight Rhodes Scholars, three governors, and countless business leaders and innovators. Its distinctive PEAK Curriculum challenges students to attain competency in the four knowledge peaks of humanities, natural sciences, social sciences, and a professional field—empowering them to earn a major and three minors in four years. The College’s close-knit, residential campus is located in Caldwell, where its proximity both to Boise and to the world-class outdoor activities of southwest Idaho’s mountains and rivers offers unique opportunities for learning beyond the classroom. For more information, visit www.collegeofidaho.edu.